These are two newspaper articles written about Herman Bottcher. One was written as he was about to return to the front after recovering from malaria and wounds from the Battle of Buna. The second article was written after he was killed in the Philippines.

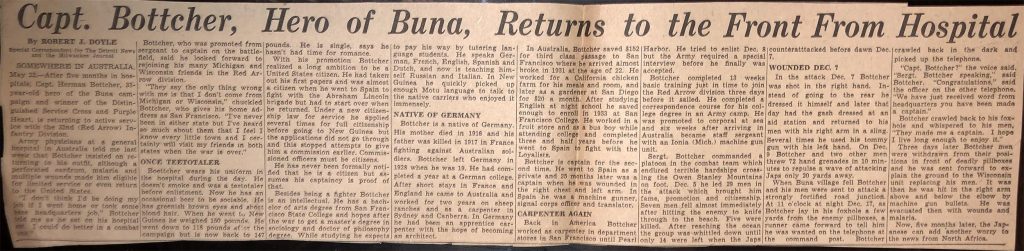

Capt. Bottcher, Hero of Buna, Returns to the Front From Hospital

By Robert J. Doyle

Special Correspondent for The Detroit News and the Milwaukee JournalSOMEWHERE IN AUSTRALIA, May 22.–After five months in hospitals, Capt. Herman Bottcher, 33-year-old hero of the Buna campaign and winner of the Distinguished Service Cross and Purple Heart, is returning to active service with the 32nd (Red Arrow) Infantry Division.

Army physicians at a general hospital in Australia told me last week that Bottcher insisted on returning to his outfit, although a perforated eardrum, malaria and multiple wounds made him eligible for limited service or even return to the United States.

“I don’t think I’d be doing my job if I went home or took some base headquarters job,” Bottcher told me as he sat on his hospital cot. I could do better in a combat unit.”

Bottcher, who was promoted from sergeant to captain on the battlefield, said he looked forward to rejoining his many Michigan and Wisconsin friends in the Red Arrow division.

“They say the only thing wrong with me is that I don’t come from Michigan or Wisconsin,” chuckled Bottcher, who gives his home address as San Francisco. “I’ve never been in either state but I’ve heard so much about them that I feel I know every little town and I certainly will visit my friends in both states when the war is over.”

Once Teetotaler

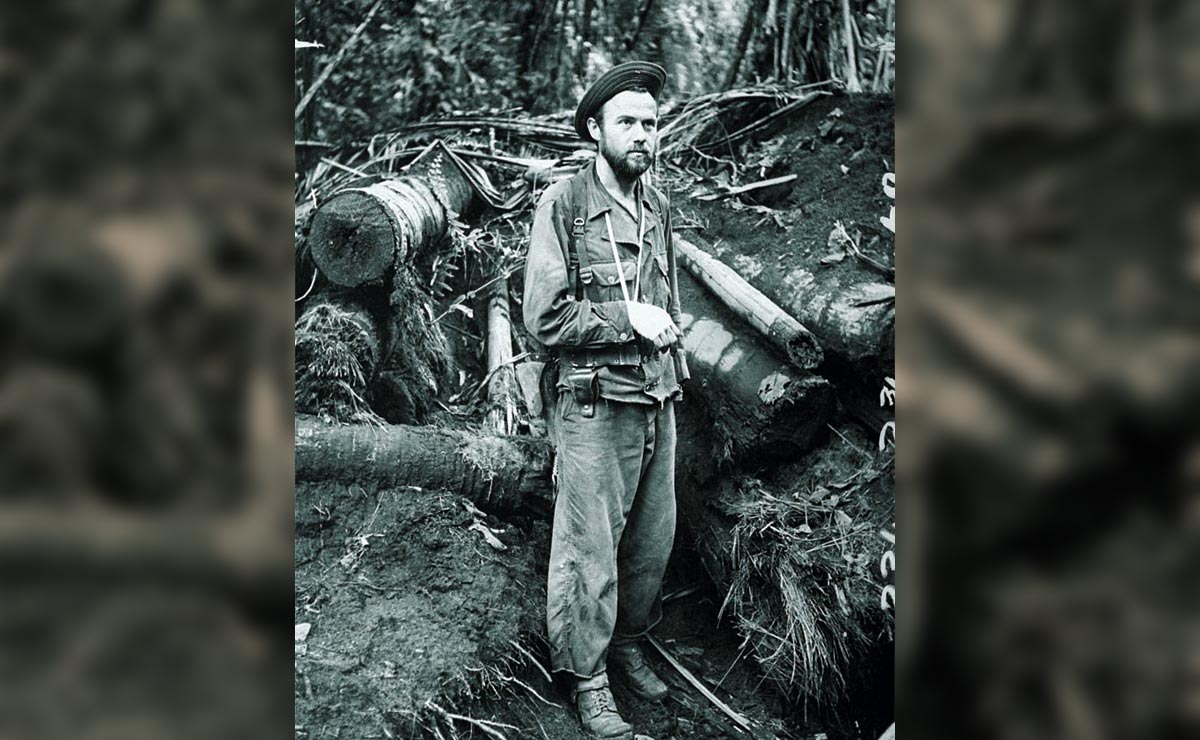

Boettcher [sic] wears his uniform in the hospital during the day. He doesn’t smoke and was a teetotaler before enlistment. Now he has an occasional beer to be sociable. He has greenish brown eyes and short blond hair. When he went to New Guinea he weighed 150 pounds. He went down to 118 pounds after the campaign but is now back to 147 pounds. He is single, says he hasn’t had time for romance.

With his promotion Bottcher realized a long ambition to be a United States citizen. He had taken out his first papers and was almost a citizen when he went to Spain to fight with the Abraham Lincoln brigade but had to start over when he returned. Under a new citizenship law for service he applied several times for full citizenship before going to New Guinea, but the applications did not go through and this stopped attempts to give him a commission earlier. Commissioned officers must be citizens.

He has never been formally notified that he is a citizen but assumes his captaincy is proof of that.

Besides being a fighter Bottcher is an intellectual. He has a bachelor of arts degree from San Francisco State College and hopes after the war to get a master’s degree in sociology and a doctor of philosophy degree. While studying he expects to pay his way by tutoring language students. He speaks German, French, English, Spanish and Dutch, and now is teaching himself Russian and Italian. In New Guinea he quickly picked up enough Motu language to talk to the native carriers who enjoyed it immensely.

Native of Germany

Bottcher is a native of Germany. His mother died in 1916 and his father was killed in 1917 in France fighting against Australian soldiers. Bottcher left Germany in 1928 when he was 19. He had completed a year at a German college. After short stays in France and England he came to Australia and worked for two years on sheep ranches and as a carpenter in Sydney and Canberra. In Germany he had been an apprentice carpenter with the hope of becoming an architect.

In Australia, Bottcher saved $152 for third class passage to San Francisco where he arrived almost broke in 1931 at the age of 22. He worked for a California chicken farm for his meals and room, and later as a gardener at San Diego for $20 a month. After studying English at night school he saved enough to enroll in 1933 at San Francisco College. He worked in a fruit store and as a bus boy while attending college and completed three and a half years before he went to Spain to fight with the Loyalists.

Bottcher is captain for the second time. He went to Spain as a private and 25 months later was a captain when he was wounded in the right chest and left arm. In Spain he was a machine gunner, signal corps officer and translator.

Carpenter Again

Back in America Bottcher worked as carpenter [sic] in department stores in San Francisco until Pearl Harbor. He tried to enlist Dec. 8 but the Army required a special interview before he was finally accepted.

Bottcher completed 13 weeks basic training just in time to join the Red Arrow division three days before it sailed. He completed a correspondence course for his college degree in an Army camp. He was promoted to corporal at sea and six weeks after arriving in Australia became staff sergeant with an Ionia (Mich.) machine gun unit.

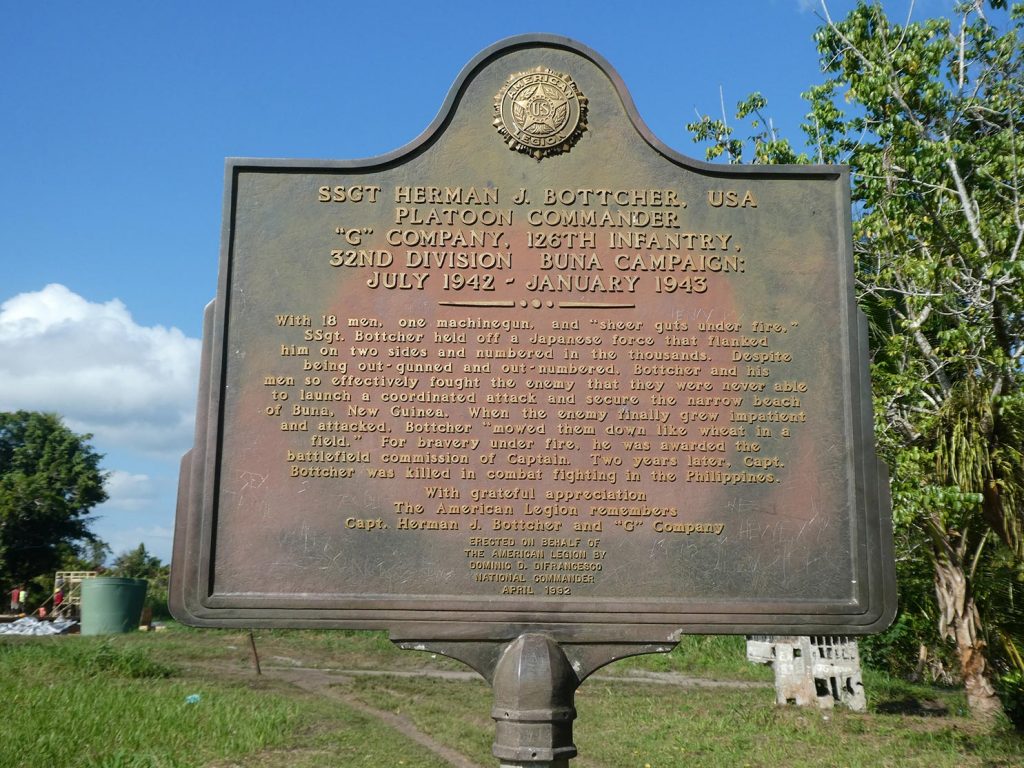

Sergt. Bottcher commanded a platoon in the combat team which endured terrible hardships crossing the Owen Stanley Mountains on foot. Dec. 5 he led 29 men in the attack which brought him fame, promotion and citizenship. Seven men fell almost immediately after hitting the enemy to knife through to the beach. Five were killed. After reaching the ocean the group was whittled down until only 14 were left when the Japs counterattacked before dawn Dec. 7.

Wounded Dec. 7

In the attack Dec. 7 Bottcher was shot in the right hand. Instead of going to the rear he dressed it himself and later that day had the gash dressed at an aid station and returned to his men with his right arm in a sling. Several times he used his tommy gun with his left hand. On dec 9 Bottcher and two other men threw 72 hand grenades in 10 minutes to repulse a wave of attacking Japs only 20 yards away.

When Buna village fell Bottcher and his men were sent to attack a strongly fortified road junction. At 11 o’clock at night Dec. 17, as Bottcher lay in his foxhole a few yards from the enemy pillboxes, a runner came forward to tell him he was wanted on the telephone at the command post. Bottcher crawled back in the dark and picked up the telephone.

“Capt. Bottcher?” the voice said. “Sergt. Bottcher speaking,” said Bottcher. “Congratulations,” said the officer on the other telephone. “We have just received word from headquarters you have been made a captain.”

Bottcher crawled back to his foxhole and whispered to his men, “They made me a captain. I hope I live long enough to enjoy it.”

Three days later Bottcher men [sic] were withdrawn from their positions in front of deadly pillboxes and he was sent forward to explain the ground to the Wisconsin unit replacing his men. It was then he was hit in the right arm above and below the elbow by machine gun bullets. He was evacuated then with wounds and malaria.

Now, five months later, the Japanese can add another worry to the news from North Africa. 1

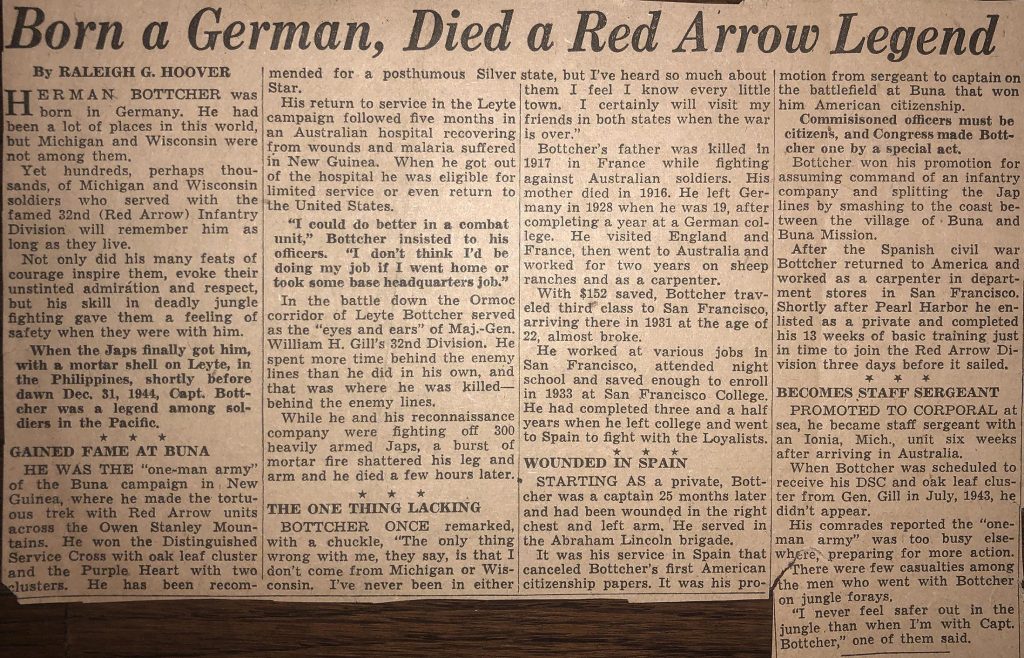

Born a German, Died a Red Arrow Legend

By Raleigh G. Hoover

Herman Bottcher was born in Germany. He had been a lot of places in this world, but Michigan and Wisconsin were not among them.

Yet hundreds, perhaps thousands, of Michigan and Wisconsin soldiers who served with the famed 32nd (Red Arrow) Infantry Division will remember him as long as they live.

Not only did his many feats of courage inspire them, invoke their unstinted admiration and respect, but his skill in deadly jungle fighting gave them a feeling of safety when they were with him.

When the Japs finally got him, with a mortar shell on Leyte, n the Phillippines, shortly before dawn Dec. 31, 1944, Capt. Bottcher was a legend among soldiers in the Pacific.

Gained Fame at Buna

He was the “one-man army” of the Buna campaign in New Guinea, where he made the tortuous trek with the Red Arrow units across the Owen Stanley Mountains. He won the Distinguished Service Cross with the oak leaf cluster and the Purple Heart with two clusters. He has been recommended for a posthumous Silver Star.

His return to service in the Leyte campaign followed five months in an Australian hospital recovering from wounds and malaria suffered in New Guinea. When he got out of the hospital he was eligible for limited service or even return to the United States.

“I could do better in a combat unit,” Bottcher insisted to his officers. “I don’t think I’d be doing my job if I went home or took some base headquarters job.”

In the battle down the Ormoc corridor of Leyte Bottcher served as the “eyes and ears” of Maj.-Gen. William H. Gill’s 32n Division. He spent more time behind the enemy lines that he did in his own, and that was where he was killed – behind the enemy lines.

While he and his reconnaissance company were fighting off 300 heavily armed Japs, a burst of mortar fire shattered his leg and arm and he died a few hours later.

The One Thing Lacking

Bottcher once remarked with a chuckle, “The only thing wrong with me, they say, is that I don’t come from Michigan or Wisconsin. I’ve never been in either state, but I’ve heard so much about them I feel I know every little town. I certainly will visit my friends in both states when the war is over.”

Bottcher’s father was killed in 1917 in France while fighting against Australian soldiers. His mother died in 1916. He left Germany in 1928 when he was 19, after completing a year at a German college. He visited England and France, then went to Australia and worked for two years on sheep ranches and as a carpenter.

With $152 saved, Bottcher traveled third class to San Francisco, arriving there in 1931 at the age of 22, almost broke.

He worked at various jobs in San Francisco, attended night school and saved enough to enroll in 1933 at San Francisco College. He had completed three and a half years when he left college and went to Spain to fight with the Loyalists.

Wounded in Spain

Starting as a private, Bottcher was a captain 25 months later and had been wounded in the right chest and left arm. He served in the Abraham Lincoln brigade.

It was his service in Spain that canceled Bottcher’s first American citizenship papers. It was his promotion from sergeant to captain on the battlefield at Buna that won him American citizenship.

Commissioned officers must be citizens, and Congress made Bottcher one by a special act.

Bottcher won his promotion for assuming command of an infantry company and splitting the Jap lines by smashing to the coast between the village of Buna and Buna Mission.

After the Spanish civil war Bottcher returned to America and worked as a carpenter in department stores in San Francisco. Shortly after Pearl Harbor he enlisted as a private and completed his 13 weeks of basic training just in time to join the Red Arrow Division three days before it sailed.

Becomes Staff Sergeant

Promoted to corporal at sea, he became staff sergeant with an Ionia, Mich., unit six weeks after arriving in Australia.

When Bottcher was scheduled to receive his DSC and oak leaf cluster from Gen. Gill in July, 1943, he didn’t appear.

His comrades reported the “one-man army” was too busy elsewhere, preparing for more action. There were few casualties among the men who went with Bottcher on jungle forays.

“I never feel safer out in the jungle than when I’m with Capt. Bottcher,” one of them said.2

Herman Bottcher is buried in the Manila American Cemetery and Memorial. There is a plaque with details of his heroics near the beach at Buna in Papua New Guinea.

- “Capt. Bottcher, Hero of Buna, Returns to the Front From Hospital.” Clipping from unknown newspaper, 1943.

- “Born a German, Died a Red Arrow Legend.” Clipping from unknown newspaper, 1945.

0 comments